By Julia Cardi

A little more than a year into Denver’s program designed to redirect emergency calls more suited for social services than police, none of those redirected calls have resulted in arrests .

The civilian-centered Support Team Assisted Response program sends pairs of mental health clinicians and paramedics to low-level, nonviolent situations after a 911 dispatcher screens calls and determines the appropriate response. STAR has responded to more than 1,600 calls since it began operating in June 2020, according to data presented Monday to Denver City Council’s Budget and Policy Committee.

Of those responses, 476 homeless people were contacted in encampments and 111 people were connected with services through the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, The Gathering Place and the Department of Human Services. Social worker and addiction counselor Carleigh Sailon said although 45% of people contacted were not yet ready to consider social services for their situations, 33% of calls resulted in transport to homeless shelters, crisis centers or other services.

Sailon now manages STAR’s operations and formerly worked at the Mental Health Center of Denver, with which the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment is currently negotiating a contract for STAR’s operations.

Amid more than a year of heightened debates about how broad a role police should have beyond strictly law enforcement, the STAR program has stood out as a rare instance of reducing its role that police and those who push for reform agree on.

“I realized that there are different definitions about what defunding the police means. And I think that this conversation is at the core of what defunding the police means,” said District 10 Councilmember Chris Hinds, one of STAR’s most vocal supporters, speaking to the complexity of meanings that even supporters of the movement ascribe to it.

The program has received $2.4 million for a currently planned expansion of STAR between a supplemental allocation from the city budget and the Caring for Denver Foundation.

The planned expansion of STAR means the program will provide responses to calls citywide and expand its operating times up to 16 hours per day, seven days a week, said Jeff Holliday, who manages the Office of Behavioral Health Strategies at the Department of Public Health and Environment.

Sailon added that so far, 911 dispatch has relied on seven designated call “nature codes” to determine which calls are appropriate for a STAR response. She said the hope is the program expands to use more details of each individual call to decide whether STAR should respond.

Sailon said calls for trespassing, welfare checks and assists have so far been the three most common situations STAR has responded to.

“We will continue to use data to drive the expansion and make sure that we’re doing so in an equitable way so that the community has access to civilian response and resource connection,” she said.

The Department of Public Health and Environment is negotiating a contract with the Mental Health Center of Denver for STAR’s operations, and the program is in the process of moving out of the umbrella of the police department.

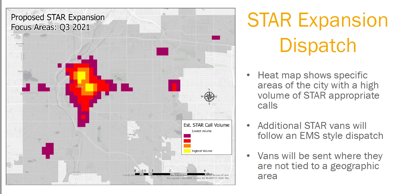

The presentation included a map showing the STAR responses tracked so far are heavily concentrated around downtown Denver and surrounding neighborhoods. Sailon said the program responds to a high volume of calls along East Colfax Avenue, South Federal Boulevard and the Montbello area.

District 6 Councilmember Paul Kashmann pointed out the map suggests there isn’t a need for STAR in other areas of the city, which he said he’s sure isn’t true.

Holliday agreed, and said data collection so far has relied solely on 911 calls. He said one intention of STAR’s expansion is to include consideration of more ways to access the program because of the stigma attached to calling 911.

“If there’s a reason that we have cops in every corner of the city, [for] that same reason we should have STAR,” Kashmann said.

Tracking data will be one role of a 15-member advisory committee for STAR designed to work with the Department of Public Health and Environment. Holliday said the committee’s tasks will also include outreach to create community awareness of STAR and review feedback on the program.

The committee includes members representing each City Council district, who can serve up to two three-year terms.

The committee’s first meeting will take place on Sept. 14 at Carla Madison Recreation Center and virtually.