Healing doesn’t begin the moment trauma ends. For many survivors of sexual or domestic violence, trafficking, and other types of interpersonal harm, that’s when the hardest work actually starts—addressing the trauma this violence leaves. Our grantee partners, Wings, Voluntad, and Latina Safehouse met to support shared learning and connection among providers, organizations, and people doing work in the survivor space. In their session, they were able to explore three questions:

Based on their experience and expertise, they shared what it actually takes to improve mental health for survivors — the challenges, the breakthroughs, and what must exist for healing to take root.

What does it look like to help facilitate shifts in mental health for survivors?

Improved mental health and healing from trauma caused by interpersonal violence are not defined by a single moment or outcome. For survivors, change often happens gradually in how they relate to themselves, others, and the world around them. These shifts are not always visible in traditional metrics, but they do indicate meaningful indicators of progress. Wings, Voluntad, and Latina SafeHouse named six shifts to indicate a survivor’s mental health is improving and that they are engaging in healing.

Feeling Safer to Trust and Talk About Mental Health

Healing often begins with having the space to acknowledge the experiences that created trauma in the lives of survivors and being able to speak about these safely. Unfortunately, many survivors of sexual or domestic violence and trafficking face denial, disbelief and victim-blaming from both external forces and internalized beliefs, which deepen feelings of shame and silence. Without information about how prevalent these issues are, many survivors may not even realize that what they experienced was relational harm – and that it may have serious impacts to their mental health.

A true shift in healing requires accessing education that can help survivors start to make these connections, so they can move from shame to self-compassion. It means reshaping the internal narrative from “This happened because of me” to “This happened to me.” It also means being able to access services and support on a regular basis that can help survivors heal the impacts of the violence they experienced over time. This may lead to outcomes such as survivors beginning to feel safe and present in their bodies again, no longer feeling disconnected or disembodied as they move through daily life.

Taking Ownership of One’s Own Healing and Needs

On the healing journey, autonomy is key. Providing essential information and resources that allow survivors to grow in knowledge, while having choice, supports their ability and increases their confidence in advocating for themselves. This may support them in making new choices regarding identifying the relationships they want to be in, setting boundaries, and asking for what they need to feel safe and supported.

Often, survivors need help navigating where and how to access care and resources. While ownership of healing can show up in practical ways — such as managing healthcare, making appointments, or seeking support independently — many survivors, particularly those from marginalized communities, face systemic barriers that limit access to these options. Despite a strong desire for autonomy, structural inequities related to cost, language, immigration status, discrimination, or availability of services can make self-advocacy difficult to realize in practice. In this context, ownership of healing may begin internally: survivors recognizing, trusting, and reconnecting with their own agency, even when systems are not yet fully accessible. With the right supports in place, survivors are better able to take an active role in decisions about their care and healing.

Seeing oneself with compassion and confidence

As survivors begin to acknowledge their trauma and seek support, they often face the work of rebuilding confidence and reclaiming a positive sense of self. It can be easy for survivors to feel like they are stuck in a constant state of need, focused on survival and rebuilding. However, it is just as important to recognize how far survivors have already come and how much they have to offer.

There are survivors who long to feel seen and validated before they are ready to seek support, while others may be receiving services, yet may still struggle to see their own worth. The truth is that while they may have been impacted by the experiences that happened to them, survivors are still whole. They remain deserving of joy, love, dignity, and all the goodness of life.

Real change, then, is not only about seeking help, but about recognizing one’s own worthiness of joy, purpose, and connection. It looks like becoming more integrated within oneself: feeling safer in the body, sensing that joy is accessible again, and beginning to find meaning in life beyond survival.

Feeling More Grounded and Self-Aware

Another key shift in healing is a growing sense of grounding and self-awareness. As survivors become more integrated within themselves, they begin to better understand how trauma has shaped the way they move through the world. This includes developing insight into how experiences such as trafficking or childhood abuse have influenced their relationships, worldviews, and sense of safety.

This awareness allows survivors to identify personal triggers and vulnerabilities, set healthy boundaries, and hold both themselves and others accountable. Many also begin developing skills for regulating their nervous systems during moments of stress, fear, or feeling overwhelmed.

For those navigating substance use or other addictive behaviors, improved self-awareness can mean understanding the underlying trauma connected to those behaviors. Rather than responding with shame, survivors can approach their healing with curiosity, compassion, and a growing sense of control.

Recognizing and Expressing Emotions in Healthy Ways

Healing is not linear, and it’s ok to not be ok. The win is being able to create space to feel, name, and process emotions safely. This looks like moving from intellectualizing feelings to genuine vulnerability with oneself and others. This includes openly speaking about how they are feeling and allowing space for others to do so.

There’s a shift from just survival to creating healthy coping skills, processing trauma, and allowing for emotional release. A shift isn’t releasing by forgetting the harm, but using tools to work through the trauma to allow space for hope, increased vitality, and a broader, more future-oriented way of thinking, being and relating. This builds mental and emotional flexibility, creating the ability to rewrite and reframe narratives to adapt and imagine a life beyond harm—and the emotional body to build, maintain and enjoy it.

Being More Open to Relationships and Community Support

As survivors begin to feel safer in their bodies, many also become more open to connection. Healing happens in community, and improved mental health often looks like feeling less isolated and having relationships with others. This may even include survivors with shared lived experience. There’s a bidirectional flow of being able to receive support from others, while also offering love, joy, and support back to their communities. This may show up through stronger friendships, healthier parenting, and deeper engagement with others. Ultimately, the hope is that survivors feel safe in their bodies again and trust that joy is accessible — not only within themselves, but through relationships, belonging, and shared healing.

What Gets in the Way of Healing?

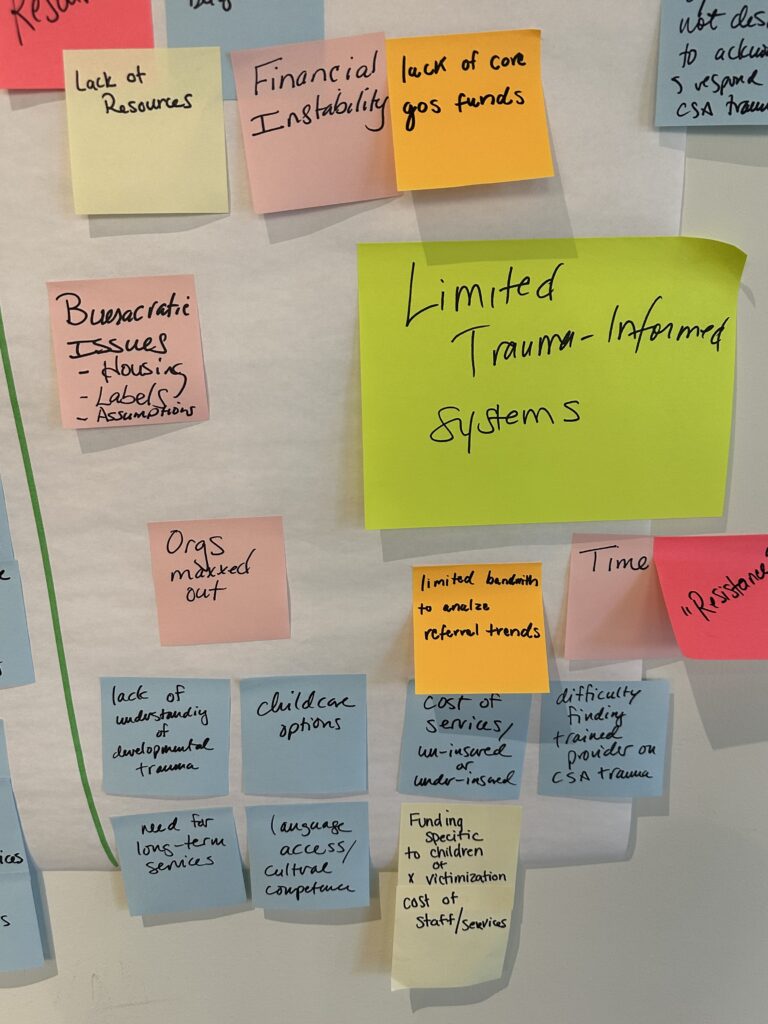

Despite these pathways toward healing, many survivors face significant barriers to accessing and sustaining care. Wings, Voluntad, and Latina SafeHouse identified six key challenges that prevent survivors from seeking or receiving quality mental health and substance misuse support.

Rigid Metrics and Practices

Many mental health and social service providers are not designed to reflect the full range of survivor experiences. Healing is non-linear, emotional, and a slow process. These rigid systems and lack of patience can sometimes lead to survivors falling through the cracks.

Funding and evaluation systems often prioritize crisis-based, short-term services. Healing from the harms of interpersonal violence, much of which occurs at developmental ages, is a slow, delicate process requiring specialized, long-term support. As survivors begin to address unresolved trauma, emotional experiences may intensify before they stabilize, and progress may not immediately resemble “improvement” as defined by traditional measures. In some cases, survivors move from functioning through survival and logistics to genuinely feeling and processing emotions for the first time — which can feel destabilizing, even as it represents meaningful emotional movement. Sometimes, addressing the impacts of unresolved trauma mean that things feel “worse” before they feel “better.” Because these shifts do not always show up in standard data metrics right away, systems that lack flexibility and patience risk misinterpreting growth as stagnation, rather than recognizing it as an essential part of healing.

Additionally, most services are time-limited, despite healing often requiring years, not months. As funding becomes increasingly narrow and crisis-focused, survivors with complex needs are more likely to fall through the cracks.

Stigma and Lack of Trust

Stigma and shame remain powerful barriers to keeping people from seeking support. Some cultures and communities don’t want to talk about sexual and domestic violence and the trauma it causes; they may even deny it entirely. Survivors may have an internal “resistance”, such as rage, fear, and past harm or current harm, so we have to meet people where they are, and that takes ample time.

Lastly, there’s a common distrust in many mental health and related systems for survivors, because of the fear of not being believed, supported, or even blamed. This is retraumatizing and can create further trauma. When trust is absent, support becomes inaccessible — no matter how many services exist.

Climate of Fear and Scarcity

Speaking of fear of further trauma, broader political and economic conditions have created an environment where fear and scarcity prevent survivors from seeking support. Because there is such a high need for services, there’s a belief that others need it more and fear that seeking support could put some communitities at risk. This is especially true for immigrant communities, where concerns about safety, documentation status, and language access can prevent people from engaging in support. In some cases, survivors stay in or return to unsafe housing because seeking help feels more dangerous than staying. When basic needs like housing, income, and safety are uncertain, healing becomes nearly impossible.

Lack of Resources

In general, there is simply a lack of resources. It’s difficult to focus on your mental health when access to basic needs like food, childcare, transportation, and health insurance aren’t met. One particular concern in access to long-term, safe housing. Most shelters are designed for sexual and domestic violence survivors and not survivors of trafficking, who often face added stigma and exclusion. As a result, trafficking survivors are often excluded due to harmful misconceptions — including the belief that they pose a safety risk to others in shared housing environments. These assumptions conflate survivors with perpetrators and ignore the complex, intersecting realities of trafficking, trauma, race, gender, and socioeconomic status. This stigma not only limits housing options but also reinforces isolation, making it more difficult for trafficking survivors to access the stability necessary for long-term healing.

Support groups are frequently at capacity from high demand, housing vouchers are limited, and long-term services are still rare. The loss of federal funding for survivor communities has further reduced access to support, even as demand continues to grow.

Staff Burnout

We must support the people who support survivors, and many providers are operating at or beyond capacity. High acuity needs, limited resources, and growing demand contribute to widespread burnout.

When organizations are overwhelmed, survivors may experience delayed responses or no response at all, making them less likely to continue reaching out for help. At the same time, organizations are often asked to produce extensive data to secure funding, but they don’t have the staff or bandwidth to do so.

Fair compensation, manageable caseloads, and wellness support for staff are essential to sustaining survivor-centered systems doing trauma-informed practice well.

Lack of trauma-informed systems

On this note, many systems are not designed to accommodate the realities of trauma. Survivors balance work, family, and survival needs, yet employers and institutions often lack flexibility or understanding.

Some systems screen for trauma without offering meaningful follow-up or support. Others rely on rigid processes that require survivors to repeatedly recount their experiences, which can be retraumatizing. Survivors may not always have the language to name what happened, and systems must make space for that truth.

So, how can we help?

Despite all the challenges, there is hope. Healing is possible — and it’s happening.

Support looks like restorative justice and co-authoring healing. Help looks like access to basic needs alongside behavioral healthcare and trauma recovery services, including stable housing, childcare, virtual options, and case management. Healing cannot wait until survival is secured; these supports must happen concurrently.

Our mental health and related systems must include wraparound resources. Effective care offers long-term services that extend beyond crisis response and include healthcare, trauma recovery, legal support, peer groups, and prioritize continuity of care. This only works when providers are trauma-informed, culturally responsive, and supported themselves.

Also, we should remember that survivors are overcoming challenges and harm. We should make their path easier, not harder. Access to care must be simplified, not made more difficult through excessive screening or barriers that retraumatize. Sometimes the most powerful intervention is simply saying, “I believe you. I hear you, and I want to help. What do you need?”

Flexible, trust-based funding is also essential. Organizations need the ability to adapt quickly to changing needs without restrictive limitations. Diversified funding allows programs to remain responsive and survivor-centered.

Finally, healing happens in community. We can support survivor healing by investing in collective care — shared spaces, peer support, listening, and staff wellness. When we care for those providing care, we strengthen outcomes for survivors themselves.

Healing for survivors does not happen in isolation, nor does it follow a straight line. It needs trust, safety, connection, and systems that are willing to adapt to the realities of trauma. While the barriers to care are real and complex, progress is possible when we invest in survivor-centered, trauma-informed, and community-based approaches.

By reducing stigma, expanding access to flexible resources, supporting the workforce, and trusting organizations closest to the work, we create the conditions where survivors are not only supported in crisis, but empowered to reclaim joy, hope, agency, and belonging.

Healing happens when we choose to meet survivors where they are and walk alongside them in their healing journey. When we all prioritize these goals, we support the collective healing survivors need and deserve. And we all experience greater wholeness in the process.